Pushing concrete in new and surprising directions, Neal Aronwitz’s practice yields compelling forms.

Portland designer Neal Aronowitz is a happy–and excited–man. After spending most of his professional life running his own tile-and-stone installation business (while making furniture for friends, family and private commissions in his spare time), he took a chance. “I decided that I just couldn’t not do design work,” he explains. “I had to follow the dream and see what happened.”

Aronwitz works out of his Portland studio, creating seemingly weightless furnishings.

Aronwitz works out of his Portland studio, creating seemingly weightless furnishings.

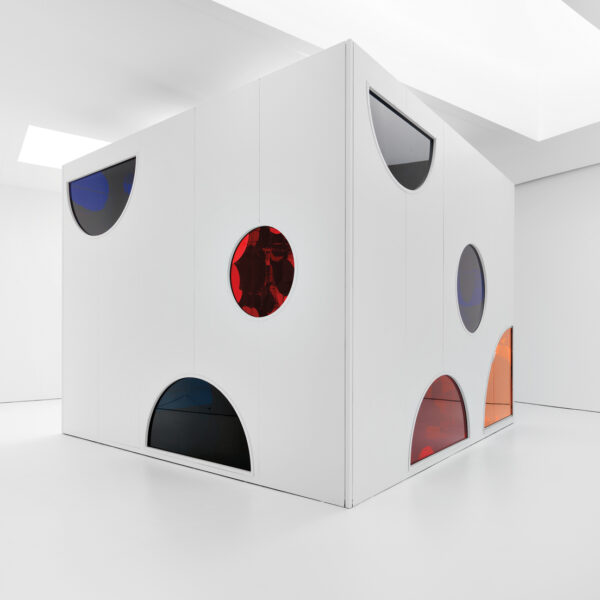

The artist's chosen medium--concrete canvas--yields solid, yet ethereal forms.

The artist's chosen medium--concrete canvas--yields solid, yet ethereal forms.

Rugged tools pepper the Portland designer's workshop.

Rugged tools pepper the Portland designer's workshop.

Aronowitz's offerings include tables and lighting that are entirely made by hand and can take upwards of 100 hours to finish, despite their deceptively simple appearance.

Aronowitz's offerings include tables and lighting that are entirely made by hand and can take upwards of 100 hours to finish, despite their deceptively simple appearance.

The moment to chase his dream arrived in 2014 when Aronowitz submitted an idea for a table to a design competition. He had seen a reference to a substance called concrete canvas on a blog and had been immediately fascinated. “I was especially intrigued by how the material could be draped over a room-sized balloon to create a shelter overnight,” he recalls. “It made me curious to explore. I like the paradox of a heavy material seeming to levitate.” He envisioned a curvaceous, self-supporting, ribbon-like coffee table–something that would appear to float even though it was made of concrete. It took months of experimentation to develop the techniques he would eventually use to mold the wet concrete canvas into the table’s sinuous shape. “I finished it the day before the show; I didn’t think I would make it,” the designer remembers. The effort paid off: “The response was incredible,” he adds.

The piece, now known as the Whorl table, became the first in a series of concrete tables and consoles, each one made by hand. “I am really interested in testing the limits of materials and mixing them in unusual ways,” Aronowitz says. “It’s so liberating to see what’s possible, to try for original forms.” To that end, his Enso table, inspired by Japanese calligraphy, combines polished aluminum and concrete canvas. “I wanted to capture dynamic movement in a static form,” he notes. “I realized very quickly that concrete canvas wouldn’t support the design I had in mind. I thought of using steel, but it seemed too heavy, so I opted for polished aluminum.” (Despite the initial challenges with steel, Aronowitz still plans to use it for upcoming versions of the table.)

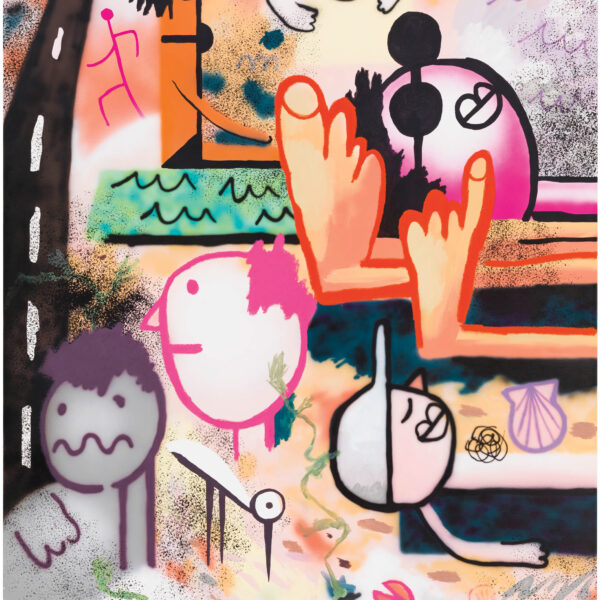

Not surprisingly for a creative who admires renowned lighting designer Ingo Maurer–and counts architect Zaha Hadid, sculptor Constantin Brancusi, plus jazz and classical music among his many influences–Aronowitz has added lighting to his repertoire. His first foray (he now has four in his collection and another three in development), the Boro Boro chandelier, is made of hand-cut borosilicate tubes. “It gives off amazing light and shadows,” he reports. “It’s so dynamic.”

Dynamic and exciting are words Aronowitz uses often, so it’s fitting that his dynamic practice is moving in some exciting directions. His work is garnering international attention, receiving awards in Germany and Great Britain; his pieces are being exhibited in galleries in Vancouver and Sag Harbor, New York; and he is in talks with galleries in San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York City. He also finds that collaborating with interior designers is a great fit for his bespoke, artisanal approach.

While the handmade figures prominently in his process, Aronowitz is actually looking at using cutting-edge three-dimensional printing technology for his next lighting series in hopes of debuting it this May at the International Contemporary Furniture Fair (ICFF) in New York. “I need excitement,” he says. “When I create a new piece, the last 5 percent is what I call the goose bump stage, where I can see that it’s going to work. That’s when I’ve captured the energy, the creative spark.” Aronowitz’s offerings include tables (left and bottom) and lighting that are entirely made by hand and can take upwards of 100 hours to finish, despite their deceptively simple appearance.